My grandmother once told me that blue was the color of Heaven. In the spring of 2024, seeing a blue outline of Mont-Saint-Michel rise above the lush green coastline of Normandy, I believed her more than I ever had before. Surely that little rock with its great church was a piece of Heaven on earth.

Some French people may agree with my description, but unfortunately many don’t. Only 37% of French people are either practicing Christians, Jews, or Muslims with any concept of Heaven. Of that 37%, most are Christian, as Christianity has a long, rich history in France. Contemporary Christianity is more complicated, as I saw firsthand during my travels to visit family. Native missionaries who understand both the history of and contemporary relationship with Christianity in Europe are necessary if we ever hope to see faith rise up like Mont-Saint-Michel still does, a thousand years after its construction.

History of Christianity in Europe

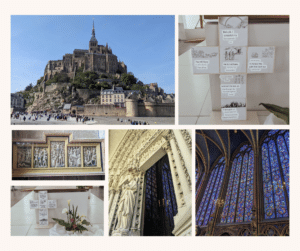

The abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy and Sainte-Chappelle in Paris both capture the incredible history of Christianity in Europe.

Mont-Saint-Michel

In 708 Catholic bishop Aubert of Avranches, a town on the Normandy coast near Brittany, saw the archangel Michael three times in a dream. The archangel supposedly told Aubert to build a sanctuary in his honor on a nearby island off the coast called Mont Tombe. He did so, and in the following years Norman dukes developed the site, creating a staggering Romanesque abbey on top of the small island and supporting monks who lived there.

Countless faithful Christians streamed to the island as pilgrims, risking their lives to cross the mudflats at low-tide. A village developed to support these pilgrims and the dukes built ramparts around the town for protection, creating the appearance of a fortified castle.

These fortifications also made it an ideal prison. During the French Revolution, the government removed the monks and redeveloped the impressive abbey into a prison. When the prison closed in the mid-1800s, locals reclaimed the island and got it recognized as a historic site. Restoration work began and monks returned roughly 100 years later in the 1960s.

A small group of monks and nuns once again live at the abbey, but the island is much more of a tourist attraction than a spiritual one. More than 2 million tourists visit each year and I was surrounded by fellow tourists since I visited on a holiday. Despite the crowds and their willingness to climb over 300 steps to get into the abbey, the book of prayers I found in the back of the church was mostly empty.

Download Pray for the Unreached prayer guide now.

Sainte-Chappelle

King Louis IX, also called King Louis the Pious, built Saint-Chappelle in the heart of Paris in the 1200s. It was his private chapel and the location of what he believed to be the crown of thorns Jesus wore during His crucifixion and a fragment of Jesus’s cross.

The chapel contains 15 rectangular stained glass windows that are almost 50 feet tall, as well as a large circular rose window, which display over 1,100 biblical scenes together. Most of the scenes are from the Catholic Old Testament, although the three windows behind the relics gallery display the line of Jesse to Jesus, Christ’s passions, John the Baptist’s life, and John the Evangelist’s life. The rose window displays scenes from Revelation.

Fires damaged the chapel in the 17th and 18th centuries, and French revolutionaries turned it into a flour warehouse. Several architects restored Sainte-Chappelle in the 19th century and moved the relics of the crown and cross to Notre Dame. Tourists like myself now flock to see Sainte-Chappelle, although most of the focus today is on the architecture, original craftsmanship, and impressive restoration work. People view the chapel as a piece of history, not a display of faith.

Contemporary Christianity in Europe

Impressive, beautiful monuments of faith display a rich history of Christianity in Europe. While many of these monuments were once sites of passionate Christian belief, most native Europeans view them purely as historic sites now. The sites provide little to no areas for faith reflection. Most educational resources focus on history and architecture instead of the eternal truths the monuments represent.

What about contemporary churches? I visited a contemporary Catholic church in Le Havre when my family’s apartment lost electricity and we needed to charge our phones. My family knew the local Catholic church had its doors open from 9 a.m. — 5 p.m. every day, and we discovered easily accessible plugs inside. I respectfully observed the church, noting burning candles in front of statues of the Virgin Mary and St. Therese of Lisieux.

In front of the central altar, there were flowers and a temporary cross with pictures and words. Translating the words from French to English, I saw that the cross depicted God’s covenant with mankind after the flood, commands to have no other gods, and reminders to give thanks for salvation, which is only available through Jesus.

As encouraged as I was by the physical openness of the church and the obvious explanation of salvation, no one else came into the church. My family and I respectfully sat in the pews for hours and never saw anyone. The next day, while we waited for the electricity technicians, we returned to the church and only saw two people. My family shared that on Sunday mornings, they only ever saw older people attending mass.

This is the unfortunate state of contemporary Christianity in Europe. The churches that are not historic sites are often empty or rapidly aging.

Hopes and Challenges of Mission Work in Europe

Since less than half of the French population are practicing Christians and most of those Christians are aging, they need native missionaries. Only native missionaries led by the Holy Spirit can help younger French generations return to the faith inheritance that surrounds them. They can bridge this historical faith with contemporary French culture, which still reflects Christian principles such as taking care of the environment and valuing family.

Forming these bridges is an essential part of mission work, which is why it’s so important to have native people do this mission work. They grew up in this post-religious culture and have better ideas for surmounting challenges than outsiders do.

French culture and contemporary Christianity is complicated, as I observed, but still hopeful. If you want to participate in this hope, download ANM’s Pray for the Unreached guide. This helpful guide provides information and prayer points for regions around the world, including Europe.